Note 5/3/2020: A few minor details of how the database functions have been changed. Refer to this post for details.

It’s been a few days since my last post, but I haven’t been idle. After spending some time consolidating the feedback I got from submitting my first attempt on reddit, I’ve returned to the basics, looking through my code and making extensive notes of what went wrong and where. And I have to say, a lot went wrong. It’s my first attempt, so I don’t want to be too hard on myself, but it’s absolutely not ready to show any employer. It’s messy and organic and clunky and I know that I’m capable of doing much better. So I’ve been spending this time redesigning the app from the ground up, and that means starting with the database.

For my first attempt, I learned pretty much only as much as necessary to make SQLAlchemy function. My database was a database in the most base sense of the word: it stored data that I gave it. By any stretch, though, it was extremely poor form. I didn’t know anything about the fundamentals of design, nothing about normal forms, nothing at all, really. And I’ve been working to rectify that this week, and I think I’ve come up with a database design that is much, much stronger.

The Goal

Like pretty much any database, this one starts with a data set that we want to represent, and a series of ways we want to manipulate that data. Because this app is fundamentally a way to extract ingredients, then the fundamental piece of data that we store in the database should represent those ingredients. Because those ingredients come from lines, and the lines make up recipes, we should probably also have database representations of them.

But that’s not all. In order to give the user as much flexibility as possible in choosing how to represent their ingredients, we need a way to change the relationship between a recipe line and the ingredients on that line. Recipe lines should be able to have an arbitrary number of ingredients, and ingredients should be able to appear on an arbitrary number of recipe lines. These areas in particular where what tripped me up so much last time; figuring out all the different ways that a recipe line could be manipulated to form different ingredients made me feel like my brain was melting out of my head. The funny thing is, of course, that all of that was essentially avoidable. A good database does that kind of work for you, something I didn’t realize before but am now applying to my design.

To round out our pre-planning phase, we should also note that we need a database representation of the grocery lists themselves (the nominal point of the whole app) and the users. Whereas last time each grocery list was linked to a specific user, this time around I’d like to leave open the option to collaborate on lists, and so I’d like each list to be able to link to an arbitrary number of users, and for each user to have an arbitrary number of lists.

So, to summarize, our database needs:

- a representation of an ingredient

- a representation of a recipe line

- a way for ingredients and lines to have shifting relationships

- a representation of a recipe, linking to an arbitrary number of lines

- a representation of a grocery list, and

- a representation of a user

With these thoughts in mind, I went through a couple of different designs, went a bit crazy with my normalization, backed it up a bit, and came up with a design that I think is pretty good.

The Design

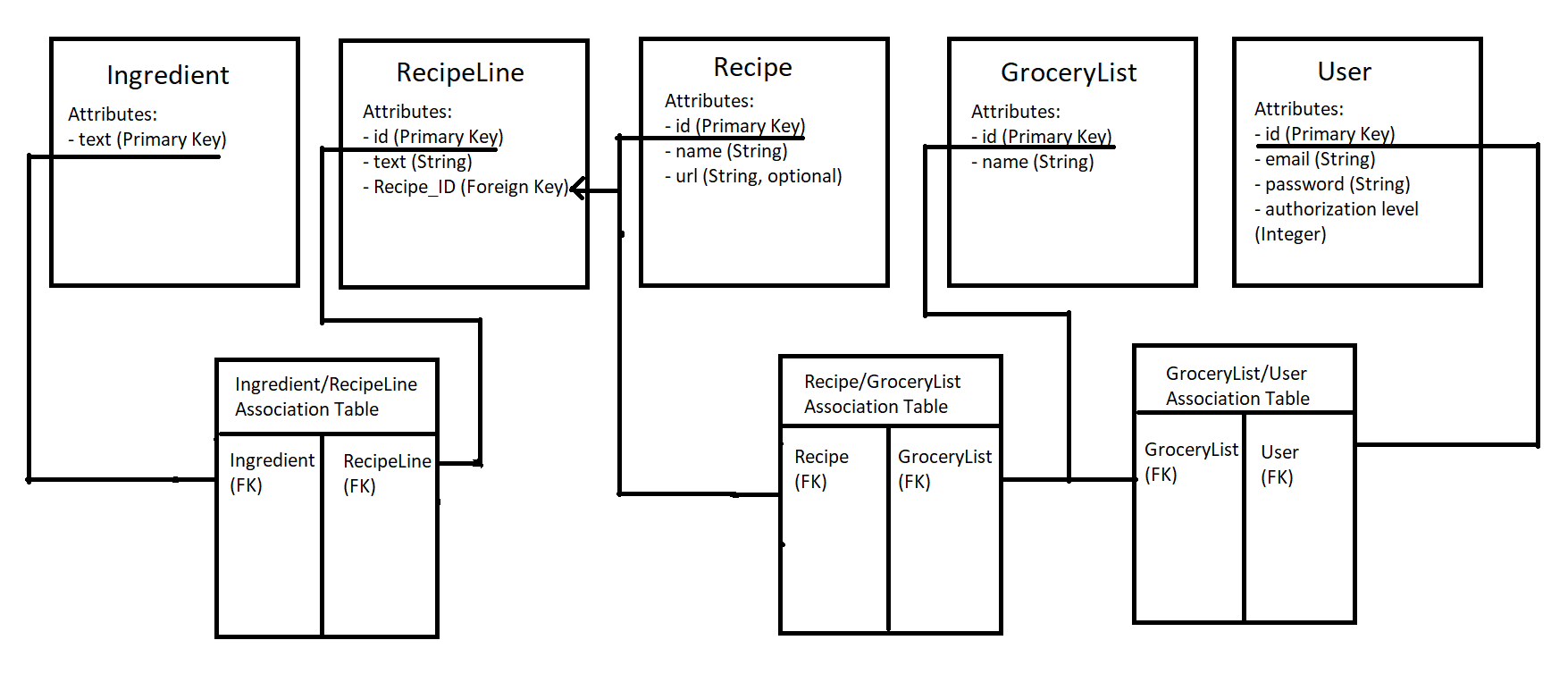

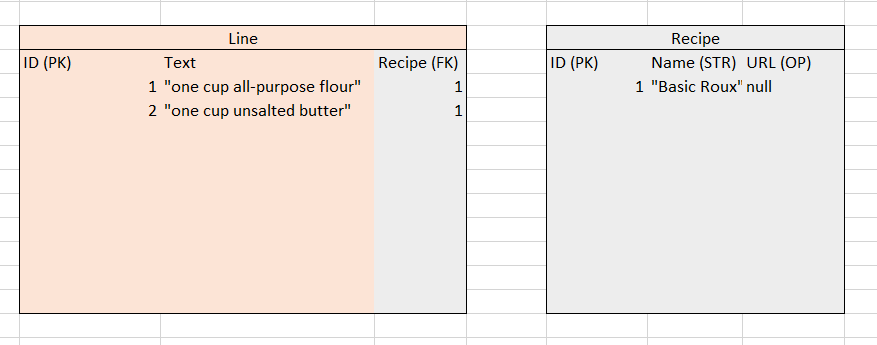

Please forgive my terrible paint skills:

This design creates five main tables, one for each of the data types we identified above:

- an

Ingredienttable for ingredients, indexed by the text of the ingredient as it’s primary key, - a

RecipeLinetable for lines in a recipe, - a

Recipetable to represent the actual recipe, - a

GroceryListtable to represent the list itself, - a

Usertable to represent the users

Additionally, there are three association tables for the many-to-many relationship that the database will need:

- one between

IngredientandRecipeLine, - one between

RecipeandGroceryList, and - one between

GroceryListandUser

There is also a many-to-one relationship between RecipeLines and a Recipe, since I don’t think I will need to reuse RecipeLines for more than one Recipe.

At first glance, much of this design may look similar to my old database, but there are several pretty extensive differences. Gone are the confusing CleanedLine and RawLine, replaced by the much simpler RecipeLine and Ingredient. More importantly, Ingredients are now shared across the database, rather than being unique to each CleanedList (which now has the much better name GroceryList). This eliminates redundant data, but more importantly automatically combines like Ingredients. Instead of having two CleanedLine entries which both read “Olive Oil”, having to check and then combine them every time a change is made to the ingredients, we can simply point both RecipeLines that contain “olive oil” to the same Ingredient. And, because GroceryLists and Ingredients aren’t directly linked, there’s no risk of data integrity problems; removing an ingredient from it’s RecipeLine automatically removes it from the associated GroceryList, and every other GroceryList that said RecipeLine is attached to. The result is a much cleaner, more streamlined representation of the data.

A Walkthrough

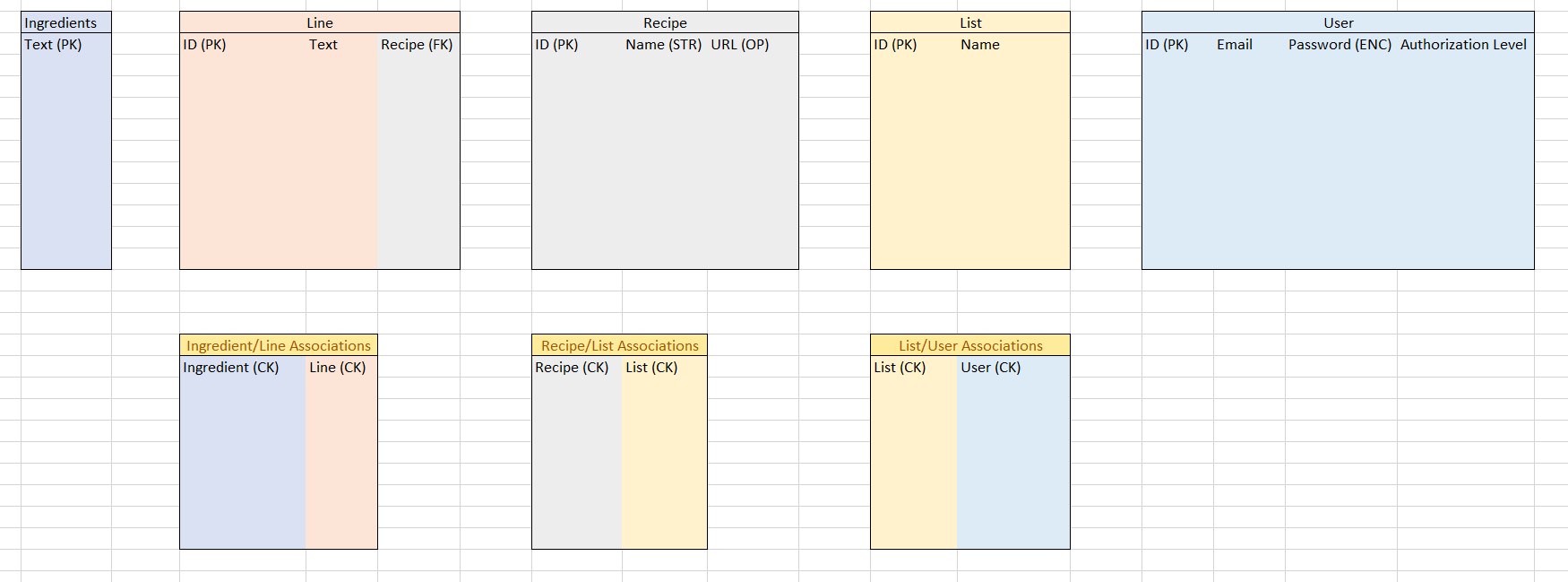

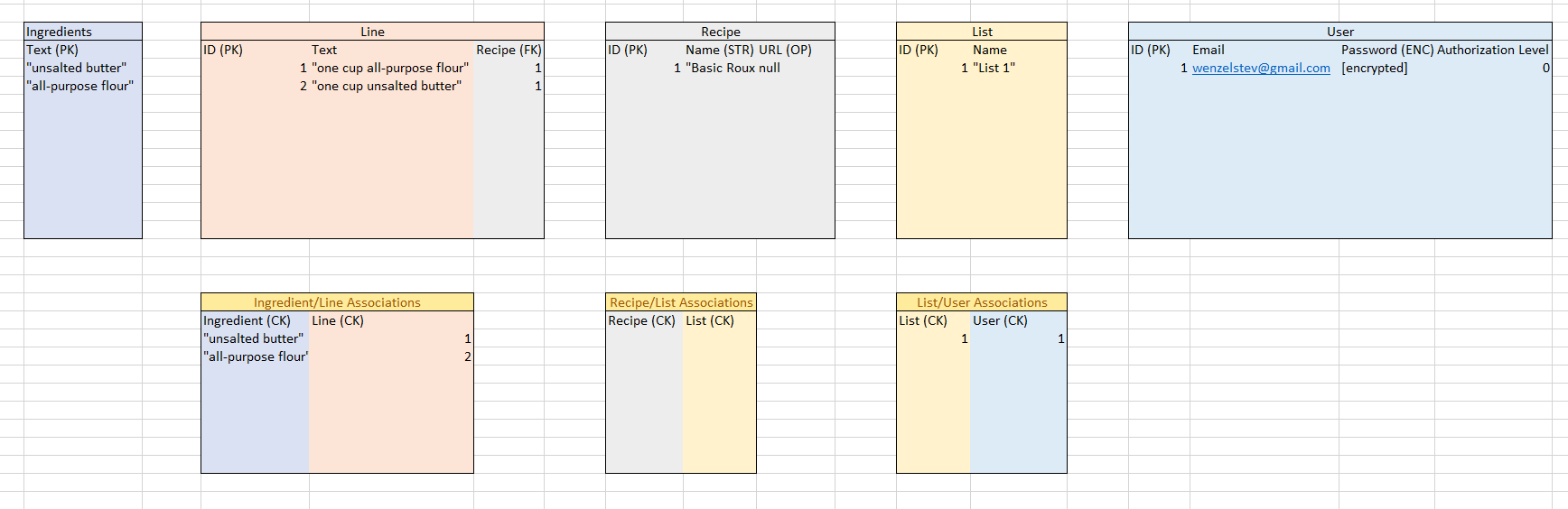

In order to give an example of how this database stores information, we’re going to insert some dummy data into a representation of the database that I’ve made in Excel. Here’s the empty database mockup:

You can see that each of the main tables is color coded, and foreign keys associated with the that table in other tables are the same color, to make the insertions easier to follow.

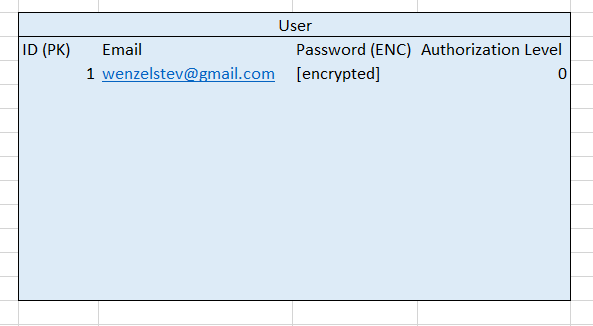

First, let’s add a new user, named… “Steve.” Unlike before, Steve does not have a username, and will simply log into his account with his email and (encrypted) password. We’ll also give Steve an authentication level of 0, since he will just be a normal user and will not have any admin privileges (more on this in a later post).

Let’s insert Steve into the Users table on the database.

Simple enough. You can see Steve’s (my) email address, some encrypted password, and the authorization level.

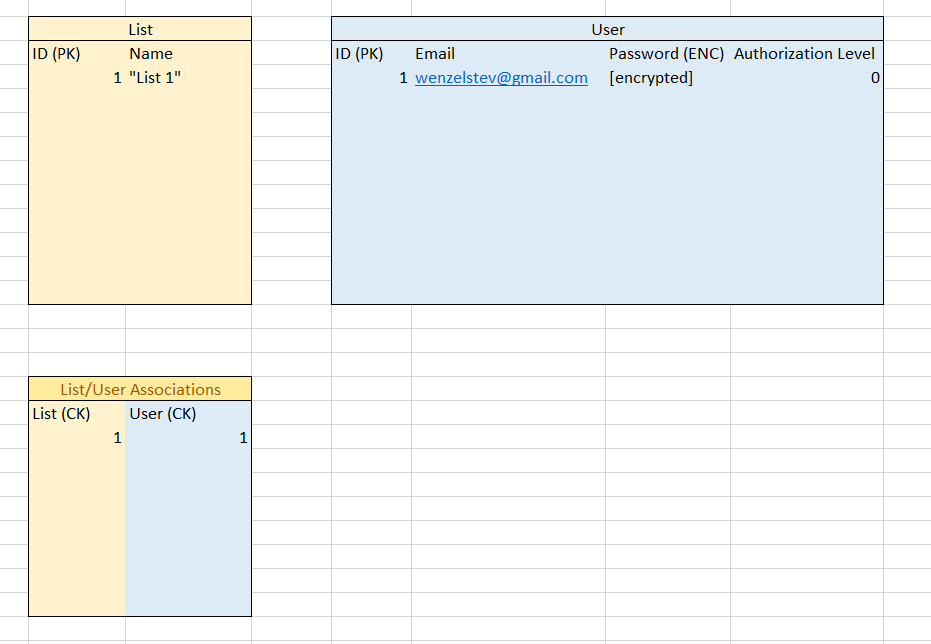

Now, let’s actually use some functionality for a list. Let’s initialize an new list for Steve, calling it “List 1.” Since Steve is creating the list, we’ll add an association between Steve and “List 1” in the Users/GroceryList association table, like so:

Still pretty simple. Our new list is initialized and given a Primary Key of 1, and in the Users/GroceryList association table, we have an association between Steve (represented by his Primary Key of 1) and “List 1” (represented by it’s Primary Key of 1).

Now it’s time to make this interesting. We’re going to add a recipe to the list. Because I’m keeping it simple, let’s use one of the easiest recipes I know, not really a recipe at all but more a base for other things: a roux. Here are the ingredients:

Basic Roux

- one cup all-purpose flour

- one cup unsalted butter

This is almost all the information needed to add the recipe to our ingredient list, but there’s just one piece missing: the program needs to know which words in the line constitute an ingredient. In the final app, we’ll be using spaCy and user input to make those determinations, but for the purposes of this exercise, we’ll just say that “unsalted butter” and “all-purpose flour” are the ingredients.

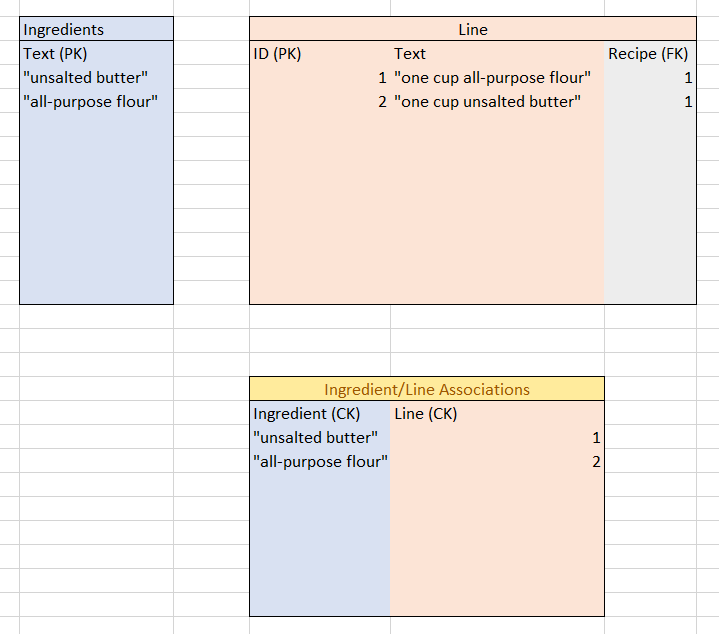

Now, a couple of things are going to happen at once. The program will insert the recipe into the Recipe table (we’ll say it has no URL), and the lines into the RecipeLine table, with the recipe’s Foreign Key inserted to show which Recipe the RecipeLines belong to.

The nice part about this database design is that none of these rows need to change. Because the associations between Ingredients and RecipeLines are in a different table, we can modify the relationships between them without having to modify any other relationships.

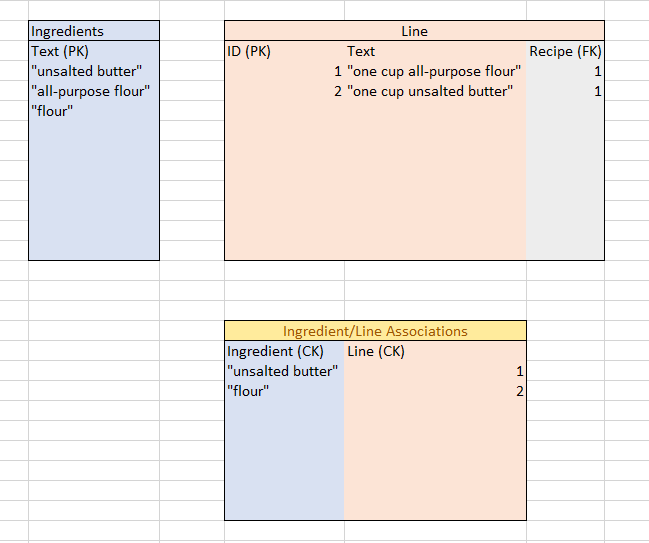

So, let’s do that now. Recall that we were given the ingredients for the row. Because we’re indexing the Ingredient table based on the string of the ingredient name itself, checking to see if “unsalted butter” and “all-purpose flour” are already in the database is easy. In this case, they aren’t, so let’s add them now. And, because we know what line they’re both on, we can add those associations to the Ingredient/RecipeLine association table.

Now, here’s the table with everything added:

And our recipe is in, and getting all ingredients in our GroceryList “List 1” is a simple set of join statements.

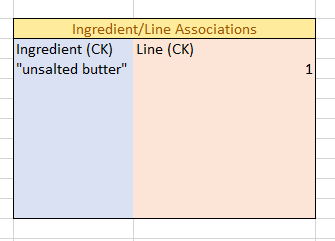

But to truly see the power of this system, let’s take this example one further. Suppose our hypothetical user has several other recipes that call for flour, and wants to combine the “all-purpose flour” ingredient with several other ingredients that all read “flour.” He makes the necessary changes on the frontend (we’ll deal with that later), and the database receives a new instruction: the Ingredient(s) on Line 1 need to change.

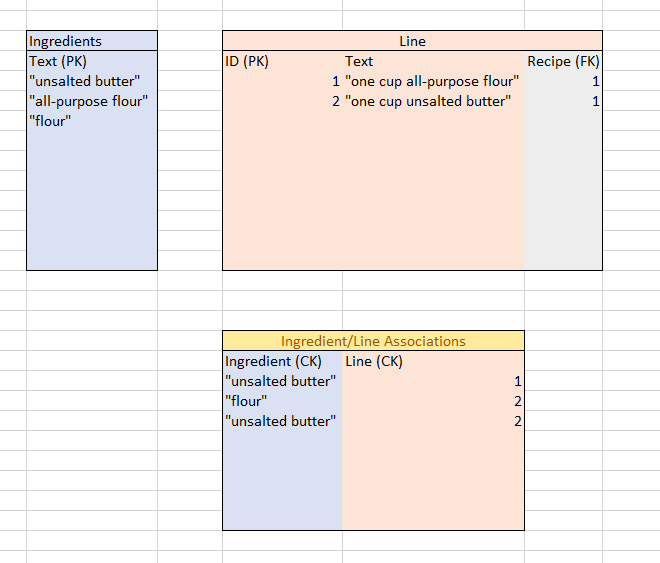

First, the program searches through the Ingredient/RecipeLine association table and deletes all associations with the line with the Primary Key of 1.

That’s all that’s needed to wipe the slate clean for that line; we don’t have to touch any other tables! Rather than mutating the ingredient “all-purpose flour” into “flour” (which we can’t do anyway because it’s a primary key), we simply scan the Ingredients table to see if an ingredient called “flour” already exists, and if not, we add it. We can then create a new pairing in the Ingredient/RecipeLine associations table, using our new ingredient.

The original “all-purpose flour” ingredient stays; it’s most likely being referenced by other RecipeLines, and even if not it will probably be referenced in the future. The point is that “all-purpose flour” as an ingredient has a single, immutable home in the entire database, and “flour” has a different, immutable home. Changing between them is as simple as changing what the RecipeLine is associated with.

There is one potential problem that’s immediately apparent, however: because the Ingredient/RecipeLine associations link an integer Primary Key, there’s no way to automatically prevent associations with ingredients that aren’t actually in the line. To continue our Roux example, it’s trivial to add another line to the Ingredient/RecipeLine association table that links “unsalted butter” with the RecipeLine “all-purpose flour:”

This is a perfectly legal insertion, even though it doesn’t make any sense to us. The actual Ingredients are meaningless to the database; it only knows associations.

The most basic way to deal with this problem is to not deal with it at all; in this world we’d write the code that updated Ingredient/RecipeLine associations such that no association between an Ingredient and a RecipeLine that didn’t house that ingredient would be made. And while it’s true that, in a perfect world our program would never try to link the ingredient “anchovies” to a line “three cups granulated sugar”, here in the real world we may not get so lucky.

Far better to implement some kind of check to make the insertion fail if the Ingredient is not in the RecipeLine. But since the database itself isn’t smart enough to do that sort of check on it’s own, the responsibility falls to us. And we’ll deal with that when we get to the actual code. But that’s for next time.