And so, with the evaluation of my heuristic model in my back pocket, it was time to bring out the big guns. I once again returned to the internet and consulted the NLP gods, and came back with a fairly straightfoward next step: it was time to try my hand at training spaCy’s NER model.

NER (Named Entity Recognition) is an aspect of Natural Language Programming that focuses on recognizing “stuff” in a body of text. This “stuff” can be whatever you want, such as names, locations, events… or in my case, recipe ingredients. Fortunately for me, spaCy comes with a fairly robust NER model, so I figured that my first order of business was to fire it up and run my test data through it, to see what I was working with.

This was easy enough:

import spacy

from first_dataset import ingredient_dataset

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

for line in ingredient_dataset:

doc = nlp(line)

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)This example, like most of the examples in this post, are copied pretty directly from spaCy’s documentation, but I’m going to explain them all as I go as best I can. doc.ents is a list of all the named entites that spaCy’s NER model picked up, and this code simply cycles through all of them found and prints relevant information about them, namely the text, the locations of the first and last character, and the category of entity.

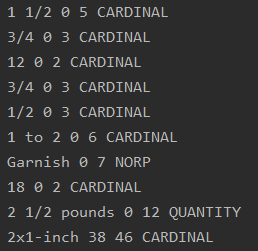

As would be expected from a list of 100 ingredient lines, this produced a lot of output, looking mostly like this:

At this point, I could already see a few things that made me pretty excited. The model was already clever enough to recognize not only numbers, but collections of numbers, as you can see in the first and sixth lines in the screenshot. 'CARDINAL' is spaCy’s category for numbers that are not associated with anything else.

The second thing that stood out was that spaCy recognized at least a few of the measurements as such, as could be seen on line 9 in the example. '2 1/2 pounds' is accurately read as a measurement, which is pretty cool. This was what got me thinking that maybe this wouldn’t be as difficult as I’d initially feared.

Finally, spaCy’s model read the word 'Garnish' as 'NORP', which according to the documentation is a category for “Nationalities or religious or political groups.” This is obviously incorrect, but I found this example particularly fascinating because I suspect that spaCy was reading “-ish” as a suffix meaning “belonging to” (e.g., English, Spanish, Danish), and thought that the word “Garnish” was referring to an individual from the illustrious country of Garn. Dungeon Masters, take note: NLP is great for worldbuilding.

But fantasy countries notwithstanding, this was already a pretty strong showing, and it gave me a good idea of where to go next. Because it seemed easier to start by updating an already existing category than creating a new one from whole cloth (although I’ll be getting to that, don’t you worry), I decided that my next step was to update spaCy’s 'QUANTITY' entity class to recognize cooking measurements. If I could get that to work, then I would move on to defining a new class for recipe ingredients.

The first thing I did was annotate some training data, using the recipe lines that I’d already collected. SpaCy’s model expects training data in a very specific style, but it was easy enough to find and copy the examples. Here’s the training set I used for my first try:

TRAIN_DATA = [

('1 1/2 cups sugar', {"entities": [(0, 10, "QUANTITY")]}),

('3/4 cup rye whiskey', {"entities": [(0, 7, "QUANTITY")]}),

('3/4 cup brandy', {"entities": [(0, 7, "QUANTITY")]}),

('1/2 cup rum', {"entities": [(0, 7, "QUANTITY")]}),

('1 to 2 cups heavy cream, lightly whipped', {"entities": [(0, 11, "QUANTITY")]}),

('2 1/2 pounds veal stew meat, cut into 2x1-inch pieces', {"entities": [(0, 12, "QUANTITY")]}),

('4 tablespoons olive oil', {"entities": [(0, 13, "QUANTITY")]}),

('1 1/2 cups chopped onion', {"entities": [(0, 10, "QUANTITY")]}),

('1 1/2 tablespoons chopped garlic', {"entities": [(0, 17, "QUANTITY")]})

]Breaking this down, we can see that the training data is stored as a list of tuples, where each tuple pairs a string with a collection of entities in the string. The entities are stored as a dictionary entry that is itself a list of tuples. In each of those tuples, there are three values: the start character of the entity, the end character of the entity, and the name of the entity category, as a string.

Confused yet? I was. I’m not entirely sure why the makers of spaCy decided on this particular format, but it’s flexible and can be pretty easily adapted to having numerous entities in a single string, or no entities.

And so, with my simple set of nine training examples, it was time to actually set up the training case. To do this, I again copied spaCy’s example model pretty much verbatim (which you can see here), going through line by line to make sure I understood it all. And I’m pleased to say that I understood the majority of it, although to be honest there are a few concepts on display that stretch my working knowledge of Python. In particular, I plan to return and better familiarize myself with decorators(@), the use of the prefix asterisk (*), and the plac module. All three of those screamed “LEARN ME BETTER” when I googled their function. I put them on my ever-growing list of “things I need to learn how to do in Python,” and continued through the example.

There’s a lot of code in the example for me to just copy over into this post (especially since you can just read it in the link above), but I do want to call attention to the most important part. Basically, the model shuffles through the examples, and for each example, it gives its best guess of the entities in the example. It then compares its guess to the annotations to see if it was right. If it was wrong, it adjusts for the next time. This is done in this section:

for itn in range(n_iter):

random.shuffle(TRAIN_DATA)

losses = {}

# batch up the examples using spaCy's minibatch

batches = minibatch(TRAIN_DATA, size=compounding(4.0, 32.0, 1.001))

for batch in batches:

texts, annotations = zip(*batch)

nlp.update(

texts, # batch of texts

annotations, # batch of annotations

drop=0.5, # dropout - make it harder to memorize data

losses=losses,

)

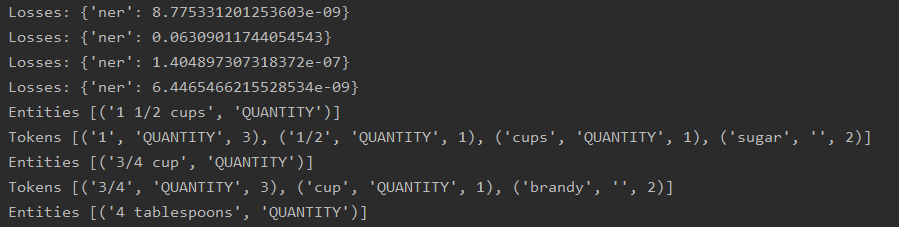

print("Losses: {}".format(losses))That’s the most important part. Most of the rest is a framework to load, save, and test the model. There are some commands that need to be run to make sure the right part of spaCy’s model is trained, and the annotations need to be added into the NER. Overall, however, the process is pretty simple. Most of the heavy lifting is done behind the scenes.

I plugged all of the necessary information in, and after a few false starts… results.

IT… IS… ALIIIIIVE!

And how! Not only is it alive, but the resultant tests showed different results! As you can see from the screenshot above, the program was successfully registering entities such as '1 1/2 cups' and '3/4 cup' as MEASUREMENTS, just like we wanted! But the real test was yet to come. Showing a changed understanding of the MEASUREMENT entity was a promising start, but all it really showed was that the model had received the training data. In order to see if it had truly learned something new, I would have to turn my model out into the harsh wilds to see how it fared.

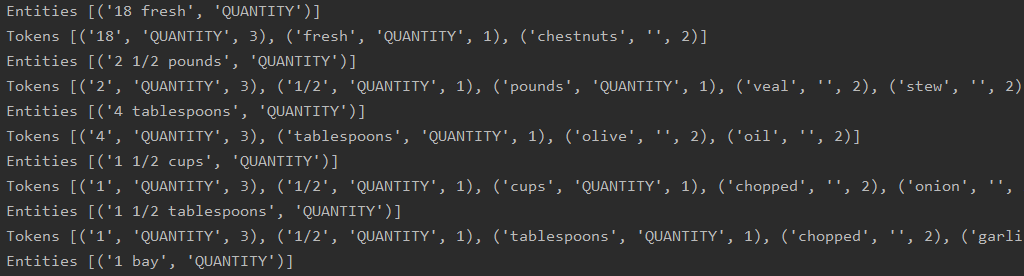

Fingers trembling, I loaded the entire set of 100 test ingredient lines into the machine, and…

It works!

… kind of. As you can see it’s getting all of the measurements right but there are a ton of false positives now; possibly the model has been updated to think that anything with a number and a word after is in fact a quantity.

I’m guessing the way to fix this is to add some examples when that isn’t true. Additionally, I noticed that some of the previous entities that spaCy picked up aren’t being picked up anymore, which might be a problem. In the documentation, they warn of “catastrophic forgetting” as an issue, when teaching the model new things causes it to forget old ones. To fix this, spaCy recommends including some examples of other entities. To be honest, I’m not sure if this is as big of a problem as it would at first seem, considering the highly specialized nature of what I want this model to do.

But this is a hell of a start.