I love to cook, but I hate grocery shopping. There’s nothing more frustrating than coming back from a long grocery run, only to find out that you’ve forgotten a crucial ingredient for that new recipe you wanted to try. This gets worse if I’m trying to meal prep, and I’ve got two or three recipes floating around in my head:

“Did I need one onion, or three?”

“I know I’ve got some flour at home, but is it enough? Should I get more?”

You get the idea.

The low-tech solution to this is an old-fashioned pen and paper, and careful rechecking to make sure that everything was copied right. But that leaves us up to human error, and besides, who has the time to write things out anymore?

No, far better to spend that time writing a program to do it for you. Besides, I needed a new project.

The Recipe Parser

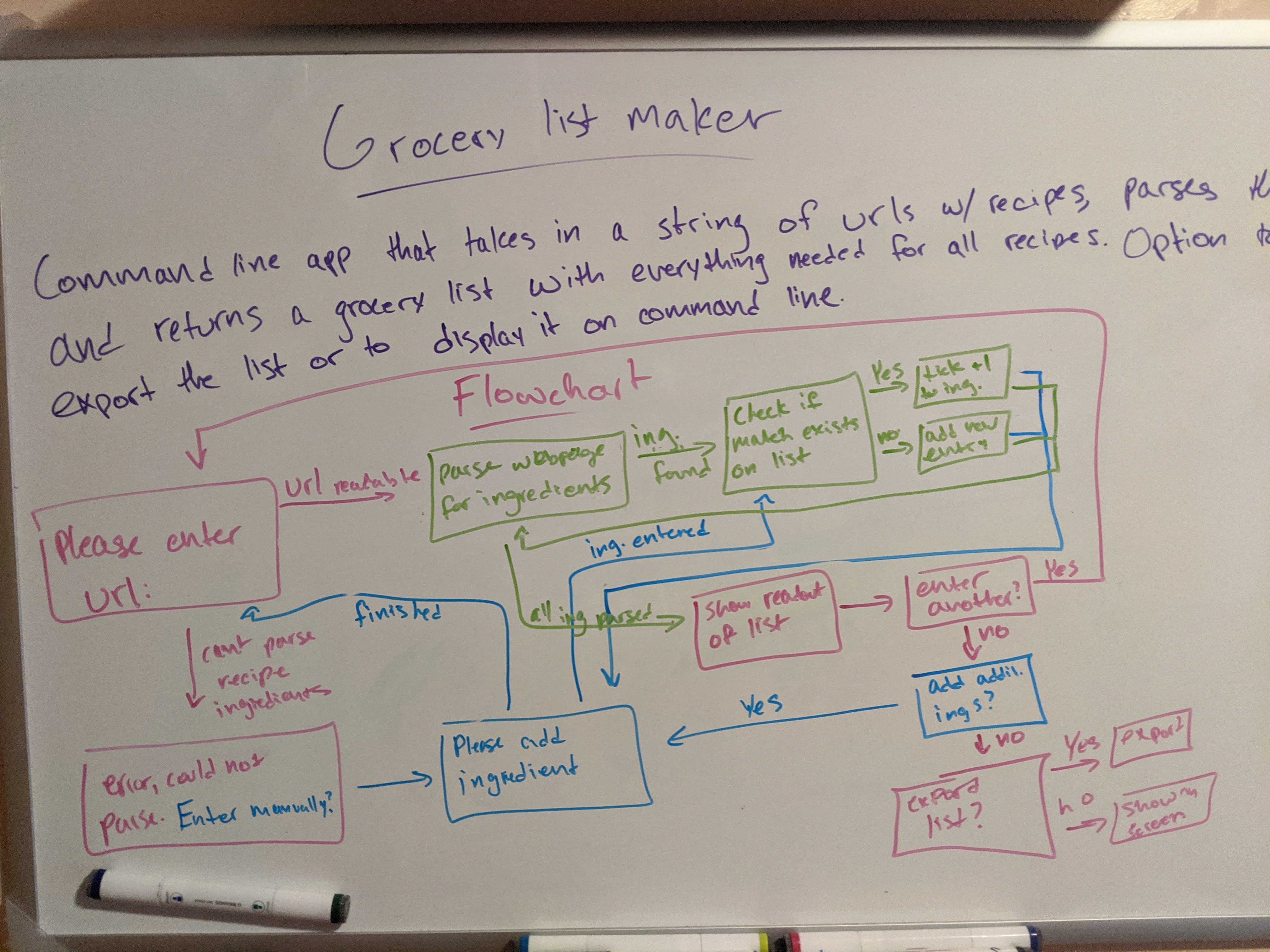

Because I’ve learned that I do much better when I externalize a problem, and because I’m trying to improve my workflow in general, I decided that I would start by mapping out the general objectives and try to build an overarching idea of how the program would run, rather than just dive in and tackle the first thing that comes to mind like I normally do.

Goal

The recipe parser is a command-line application that takes in recipe urls, parses them into a list of ingredients, and adds those ingredients to a master grocery list, combining as necessary. The grocery list can then be exported to a .txt file for easy reference.

The program will consist of several elements:

- a

beautifulsoupobject for scraping the recipe information from the website - a

shelveobject to store the grocery list - a function or class to parse the recipe lines themselves. Originally I intended this to be a regex function, but as I soon discovered, that was a poor choice.

Here you can see some of my whiteboard work, as well as a flowchart I tried to sketch out for the program. I ended up ditching a lot of this in favor of simpler command line tools, but it’s useful to show process.

At this point I felt that I was ready to enter some code.

Building the Scaffolding

I fired up Pycharm and started a new project. The intimidation of the blank page (or, in this case, blank project folder) is something that’s always gotten to me, but I focused on writing out the scaffolding as I’d planned it before:

import requests, sys, shelve

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# TODO: open a grocery list shelf/create a new one

def parse_recipe(url):

# TODO: create a beautifulsoup object to get the url

# TODO: scrape the ingredient lines from the url

# TODO: determine the amount and measurement of each ingredient

# TODO: add the ingredient into the grocery list

pass

def clear_list():

# TODO: clear the grocery list

pass

def print_list():

# TODO: create a custom print function to display the list

pass

# The main function of the program

if len(sys.argv) < 2: # if a url is not added

print("error: need a url")

elif sys.argv[1] == 'clear':

clear_list()

elif sys.argv[1] == 'print':

print_list()

else:

parse_recipe(sys.argv[1])There. Not too bad at all. A fine little scaffold of a program, if I may say so for myself. A few of the TODOs might be doing a lot of work there, but I was confident that I would be able to break them up into smaller parts when the time came.

Storing the ingredients

The next step was to fill in the easier parts of the scaffolding, implementing the shelve object and determining the format of how the grocery list would be implemented. Considering the shelve module is essentially a dictionary, I decided the best way to hold the list would be a nested dictionary, stored by ingredient, like so:

grocery_list = {'ingredient': {'measurement': 'amount'}}That way, if there was more than one measurement type for ingredient, the list could store both of them under a single entry. This left a problem, however: what about ingredients that did not have a measurement associated with them, such as eggs? To get around this, I decided to use the word “whole” as a placeholder if the ingredient did not have an associated measurement. Therefore, a recipe that called for:

- 2 eggs

- 1 1/2 cup milk

- 2 tablespoons butter

would be stored like this:

grocery_list = {

'egg': {'whole': 2}

'milk': {'cup': 1.5}

'butter': {'tablespoon': 2}

}…and so on.

Now that I’d determined just how I was going to store the ingredients, all that was left was to implement it:

# open a grocery list shelf/create a new one

grocery_list_shelf = shelve.open('grocery_list_data')

if 'grocery_list' in grocery_list_shelf: # if this is not the first time we've used the program

print('getting grocery list from file')

grocery_list = grocery_list_shelf['grocery_list']

else:

print('creating new grocery list')

grocery_list = {}

grocery_list_shelf['grocery_list'] = grocery_listNote that, even though the shelve module stores things like a dictionary, I’m storing the entire grocery list in one key, because I decided that I want the program to store the recipes that it takes the ingredients from, and maybe some other data besides.

Printing and Clearing

Finally, to round out this post, we’ll take a quick look at the clear_list() and print_list() functions, both of which are easy to implement.

For clear_list(), all I did was set the list to an empty dictionary:

def clear_list():

if 'grocery_list' in grocery_list_shelf:

grocery_list_shelf['grocery_list'] = {}

print('cleared the grocery list')For print_list(), all I did was iterate over the grocery list and return the data in the form amount measurement ingredient:

def print_list():

grocery_string = ""

grocery_list = grocery_list_shelf['grocery_list']

for k, v in grocery_list.items():

for measurement, amount in v.items():

if measurement is not None:

if amount is not 0:

grocery_string += str(amount) + " " + measurement + " "

grocery_string += k + "\n"

print(grocery_string)Which, for our above example, prints out:

2 whole egg

1.5 cup milk

2 tablespoon butter

This isn’t perfect (and doesn’t catch errors), but it’ll do for now.

And that’s all for this post! Next time I’ll tackle the actual difficult stuff, and try not to admit how long it took me to realize a regex wasn’t going to cut it for what I needed.

(You can check out the recipe parser here. Note that it’s much farther along now, but the base scaffolding can still be seen.)